Anticipation

For me, a trip is never real until the day before it starts. However, this time was a little different. I have wanted to go to Peru since I discovered leaving my country and going to another was a thing. My anticipation had been building for about 15 to 20 years. You could say I was pretty amped.

Alethea, my partner, travel buddy, and Appalachian-raised mountain momma, has always encouraged me to travel, as she grew up doing. That culminated in my first trip to Costa Rica in 2018, and after that I was hooked. Together with Alethea, her brother Jeremy, and his partner Taylor, we began planning our trip to Peru about two months in advance—researching hikes, getting trail permits, and booking lodging. Before long we had two additions to our crew, Adam and Casey, bringing us to a total of three couples.

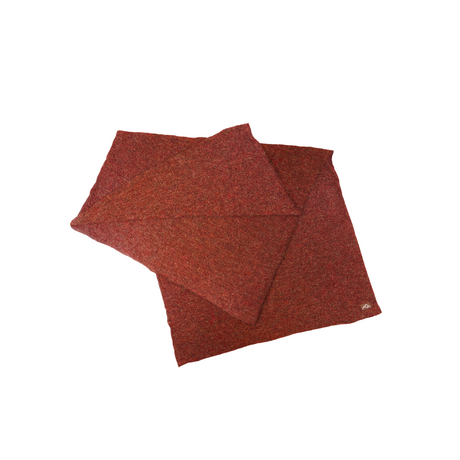

The moment that really sealed the deal for me was three nights before our flights out, when I came home to a small mound of packages, wrapped up and shipped personally by John Gage (in his finite free time) with AppGearCo hoodies, beanies, gators, buffs, and stickers. Opening those carefully wrapped boxes and distributing the goods to my friends on our last hangout before reconvening in Peru, it hit me that I was actually going to live out my childhood dream and would be hiking in the Andes the very next week.

I did not sleep the night before our 5 a.m. flight out of Richmond to Lima, and I was awake the entire flight and layover. On the second leg of our journey, I was fortuitously placed beside Silvana, an amazing Peruvian woman on her way to visit her family in Lima from the U.S. She gave me the lowdown on all the cool spots—bars with the best pisco sour and some of the better hiking trails and historical sites throughout Peru. We talked for nearly six hours. I am sure everyone on our overnight flight loved us, but I couldn’t turn down this fount of information or the endless flow of free beers I was shoving in my bookbag the whole flight.

I was about to live out my National Geographic dreams and hike mountain trails through the Andes that predate Jesus Christ walking this earth and be among indigenous peoples who have preserved their culture, language, farming, and mountaineering traditions for thousands of years. Not to mention the alpacas. This is probably the most I have ever planned for a trip, thanks to all the people involved who didn’t want to find out where they were sleeping each night about an hour before bedtime.

What We Encountered

Every part of Peru was different. The food, the people, the style of dress, the land, and even the language changed in any direction we traveled. Our first stop, Lima. The capital city of Peru sitting on the Pacific Coast was modern and buzzing with industry, fine dining, and late night lifestyles. However, there were traces of an extravagant and bohemian past that could still be seen in the coastal neighborhoods of Barranco and Miraflores—where hippies, surfers, travelers, artists, and writers gather to this day to enjoy the beaches and bars that line the cliffside city. Surfers and small fishing boats could be seen swaying on the horizon in the icy waters of the Pacific.

We then travelled south to the colonial capital city of Arequipa, our first taste of high altitude in Peru. Framed by three snow-capped volcanoes, it was almost constantly dreary and on the verge of raining, yet still beautiful. The buildings were stately and still held an aura of colonial authority. Arequipa was reminiscent of any old European city with winding cobblestone roads, large open air markets, bakeries, and various artisan shops.

Undoubtedly the best part of Arequipa for everyone was Masamama, an amazing sourdough bakery. There we fueled up on delicious rosemary focaccia sourdough bread and coca tea before heading into the southern highlands in our dinky Toyota Yaris on the highest altitude highway in the Americas, on our way to the Colca Canyon.

After a long and treacherous five hours navigating our way through the scenic route (a dirt road that was part stream, part donkey path and definitely not built for a Yaris), we ended up back on the actual road. From there we had a much more relaxing ride, aside from the occasional boulder or alpaca that had to be dodged, before making it to Yanque, a small farming village nestled in a valley between ancient pre-Incan terraces and the Colca Canyon.

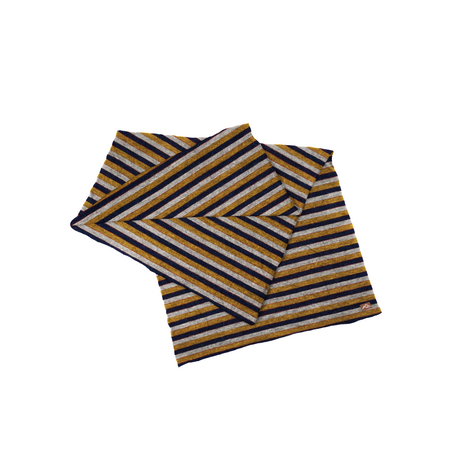

Our initial plan was to hike and climb through the Colca Canyon. However, the roads into the canyon were flooded by the extreme storms rolling through the region. Instead, we explored a town still steeped in tradition, where men and women wore a mixture of modern clothes and traditional handwoven alpaca wool and farmed hand-built terraces that extended over a thousand feet up mountainsides. They herded alpacas along the mountaintops as their ancestors had done for thousands of years before them.

The people in the southern highlands had little and worked hard in extreme conditions year-round, yet were always smiling and happy to share what they had with us. On our first day in Yanque, I watched a woman with a baby strapped across her back herd over 100 alpacas up a mountain to graze before the sun was fully risen, a testament to the power and quiet strength found in the southern highlands of Peru.

From the southern highlands we travelled to Cusco, the ancient capital of the Incan Empire and into the nearby Sacred Valley, an ancient and fertile farmland that fed the entire empire. Surrounded by mountains filled with ancient terraces and mountain top temples, villages dotted the valley floor, each specializing in something different. Our driver explained each village’s specialty to us—the first specialized in herding alpacas and harvesting their wool, another grew corn, the next made silver jewelry, and one wove textiles.

The strangest, however, was the village famed for the guinea pigs they breed for a quintessential and delicious Peruvian dish, cuy. Cuy is definitely a cultural experience. I highly recommend a smoked guinea pig, found on any roadside or restaurant around Cusco and the Sacred Valley.

Cusco itself was a center of culture and architecture, a maze of colonial streets and crumbling buildings built atop perfectly shaped and unchanging Incan architecture. Churches, museums, and textile markets were found around every corner. The city hummed with life from the bustling cafes, competing market vendors, stores, and tourists preparing to see the mystical Machu Picchu.

We took a bus from Cusco to the base of the Salkantay Trek, starting at Lago Humantay. From the ice cold lake we could see the Salkantay Pass looming thousands of feet above us, cloaked in a shroud of snow and passing storms. We camped at its base that night in an ominously torrential downpour that continued well into the next morning. We began our ascent at 5 a.m. after a light breakfast and an energizing cup of coca tea to fortify ourselves against the dizzying near 4,000-foot elevation gain we would be undertaking in just a few miles.

The hike was guided and I am glad for it, because of the maze of trails established over thousands of years of travel through the mountains. Our guide, Henricks, a native Peruvian, led us safely up the pass—choosing the most well-made bridges and the most stable trails, avoiding the mudslides that surrounded us. After we crossed the last stream, Henricks informed us that only days before a backpacker had fallen from one of the more precarious bridges we’d crossed and had drowned.

The reality and danger of the situation had not sunk in for me until that point. Despite the beauty around us and the simplicity of walking forward and upward, there can be a greater toll. Even the safest and most aware hiker can be seriously injured or die in the blink of an eye. I have seen broken bones, dehydration, hypothermia, snake bites, bad falls, mudslides, and sickness on the trail, but had never been hit by the possibility that a simple misstep or momentary loss of balance can define the line between life and death.

Despite that information we carried on with our journey, summiting at 15,100 feet of extremely difficult and technical terrain. It should be noted the people living in these highlands were running by us in crocs and flip flops in the pouring rain, leading packhorses up and down the mountains all day long. However, we were all still very proud of our summit.

From the Salkantay Pass we opted to take a longer, more scenic route to our campsite to check out another nearby glacial lake. We had to move fast, as another storm was rolling in. Our descent was in a miserable downpour, each of us just trying to stay on our feet in the constantly sliding scree and mud. We made it to our campsite soaked but alive. The waterproofing on my boots and rain jacket had long given out on me by this point, and the only warmth I had was from my alpaca hoodie (I was actually wearing two) and my wool socks. For the most part, everyone had better-suited rain gear and drier feet than I, but all of us had the alpaca hoodies on to keep the cold at bay.

On our third day of the trek, we had descended in altitude enough to be back in the rainforest and found most of the trails washed out from the storms over the past few weeks. We trudged through muck and mud, traversing narrow bridges over a deep canyon carved by an overflowing, mud-filled river that raged below us. We reached a point where there was no bridge to cross and the entire cliffside in front us had fallen into the river below. We had only one option to continue forward at this point: take what our guide Henricks called a “Peruvian zipline” across the canyon, or walk back the way we came.

We opted for the Peruvian zipline.

It amounted to essentially a cargo cart on a pulley system on high tension steel cable (with a moss covered flip flop for a friction plate on both ends,) pulled back and forth across the roughly 200 foot deep by 250 foot wide or so canyon by an extremely frayed hemp rope.

Alethea and I opted to go first. I find it easier to do stuff that scares the shit out of you if you just jump on it and she was game for it. We hopped in the swaying cart that was balanced only by our distribution of weight and could otherwise be very easily tipped over, with no other safety system or harness in place to keep us in. We were guided back across by a farmer on the other side who heaved the cart to him, while we helped from the cart, spending all of three minutes over the roaring river below.

Safely on the other side, we helped the farmer haul the rest of our crew across, taking turns on the rope with each new arrival. After we had all arrived, we continued our journey into the mountains, eventually arriving at the town below Machu Picchu.

This quickly became my least favorite part of our journey, as we were greeted by overwhelming amounts of people bused into a tourist trap of a town. It was a far shot from the serenity of the wilderness and the hospitality of the farms we had just passed through that same day.

We spent our final night of the Salkantay Trek in a mold-filled hostel before beginning our treacherous predawn hike up to Machu Picchu. The trail stretched for miles straight up the mountain, constantly crossing the switchback dirt road that brought tourists by bus to the top of the mountain, bypassing the arduous journey we were undertaking. As I watched people file off the buses and into the same lines we waited in, despite having only a 15 minute bus ride to the top, I couldn’t help but feel some sense of outrage.

I know not everyone could undertake the journey that we did, and I wholeheartedly believe all people should have access to our world heritage sites, but I found it went too far when you place a full blown cafe, gift shop, and bus station on a mountainside, barely 100 meters from one of the most awe-inspiring creations made by man that has stood for over 5,000 years.

Yet, that did not take away from the majesty of Machu Picchu, nor the sense of wonder it left me with. The massive scale of the construction combined with the perfectly balanced rocks, precisely cut to align with the sun, moon, stars, and surrounding mountain ridges, left me with so many questions.

Being at Machu Picchu is an existential crisis. How did other humans make this? How has it stood for so long? Why was it even made? Where did this knowledge of building come from? We can’t make structures like these today, with most modern technologies, yet these were constructed through banging rocks together? God? Aliens? Did humans actually de-evolve instead of evolve?

Walking through those ruins left me with many more questions than it answered. Despite walking for days in adverse weather and at high altitude, I found myself completely full of energy to explore Machu Picchu, a feeling that sustained me the whole way down from the mountaintop city, as well. It was the defining moment of our trip and the culmination of many days of travelling, getting food poisoning, hiking to the point of exhaustion, and immersing ourselves in an entirely different way of life from that found in the United States, a more ancient and traditional way that is magical and awe-inspiring.

The Good

This trip was an entire culture shift from what we are used to in the U.S. Life is still very traditional and mostly untainted by tourist culture in Peru. While you can find the touristy things to do there, you can just as easily avoid them if you want. There are breathtaking mountains where you can hike, climb, mountain bike, or relax at resorts and hotsprings. There are plenty of rivers to raft and kayak and a whole Pacific coastline for some of the best fishing and surfing in the world, alongside pristine beaches to sit back and enjoy a cold beer on. You can go to a rural farming village and enjoy the slower pace of life or just as easily make your way to a bustling city like Lima and find yourself surrounded by world class art, museums, and food. Peru has something for everyone and it's affordable if you're coming from the United States.

The Bad

The tourist culture I previously mentioned is there and to be fair, we did participate in it, to some extent. Big multinational chains, from fast food and clothing brands to rental car companies and hotel chains, can move in when they have tourists come in and shop at those places instead of local businesses.

That can put a lot of local people out of business and drive them to work for these corporations, which has a huge cultural effect. Also, there is a sense of catering to tourists. People can lose their sense of themselves and their traditions while trying to make more money from tourists. That can be avoided by shopping at real local businesses and supporting local artisans, instead of buying factory-made products.

Food also ties into this. If you want a burger, don’t go to the places you know, go to La Lucha and get an asado de res; you won’t regret it. Go traditional; eat a guinea pig. There are so many different things you can eat in Peru that you just can’t miss out on!

And The Ugly

I ate alpaca. And it was delicious. I felt pretty bad about it, wearing my AppGearCo hoodie and shirt, but I got over that and ate a lot of alpaca. It’s traditional and normal there, so no regrets.

On a more serious note, the environmental effects of tourism and travel are definitely the ugliest parts of any great journey. Your flight alone is killer on the environment, but it's often the only way to get anywhere, so you can do your best to reduce your impact while you are abroad. Peru is doing a lot to conserve its wildlife and protect endangered species, land, and water. However, there is an income and education gap alongside infrastructure challenges in the country that makes this hard.

Travelling through Peru, you can see a lot of places do not have a formal waste disposal system and are far from recycling. As we drove up into the southern highlands outside of Arequipa, we saw trucks dumping waste along the roadside, which seemed to be the norm. Piles spilled down the mountain sides like some sort of grotesque, foul-smelling avalanche (I really cannot stress enough how bad the odor was).

This pollution went past roadside cliffs and made it deep into trails as well. As we hiked through Peru, we noticed the trails to be littered with trash, even ones leading to ancient religious sites and tombs. We picked up as much as we could, but you can only take so much with you. And this is not to say that the government and people of Peru aren’t doing anything about it. This is what is left over despite the extensive efforts to curtail littering.

To end on a more positive note, the untamed mountain ranges of Peru still stand for the most part untouched. Our hike through the Salkantay Pass was unforgettable and mostly pristine, due to the efforts of the people who still reside in those mountains, living traditional lives far from modernity. They live hard lives, without much comfort based on our standards, but they are happy with what they have and serve as an inspiration for how life should be lived and appreciated. Viva El Peru!